The Power of Enemy-Love

testing the gospel of stranger danger

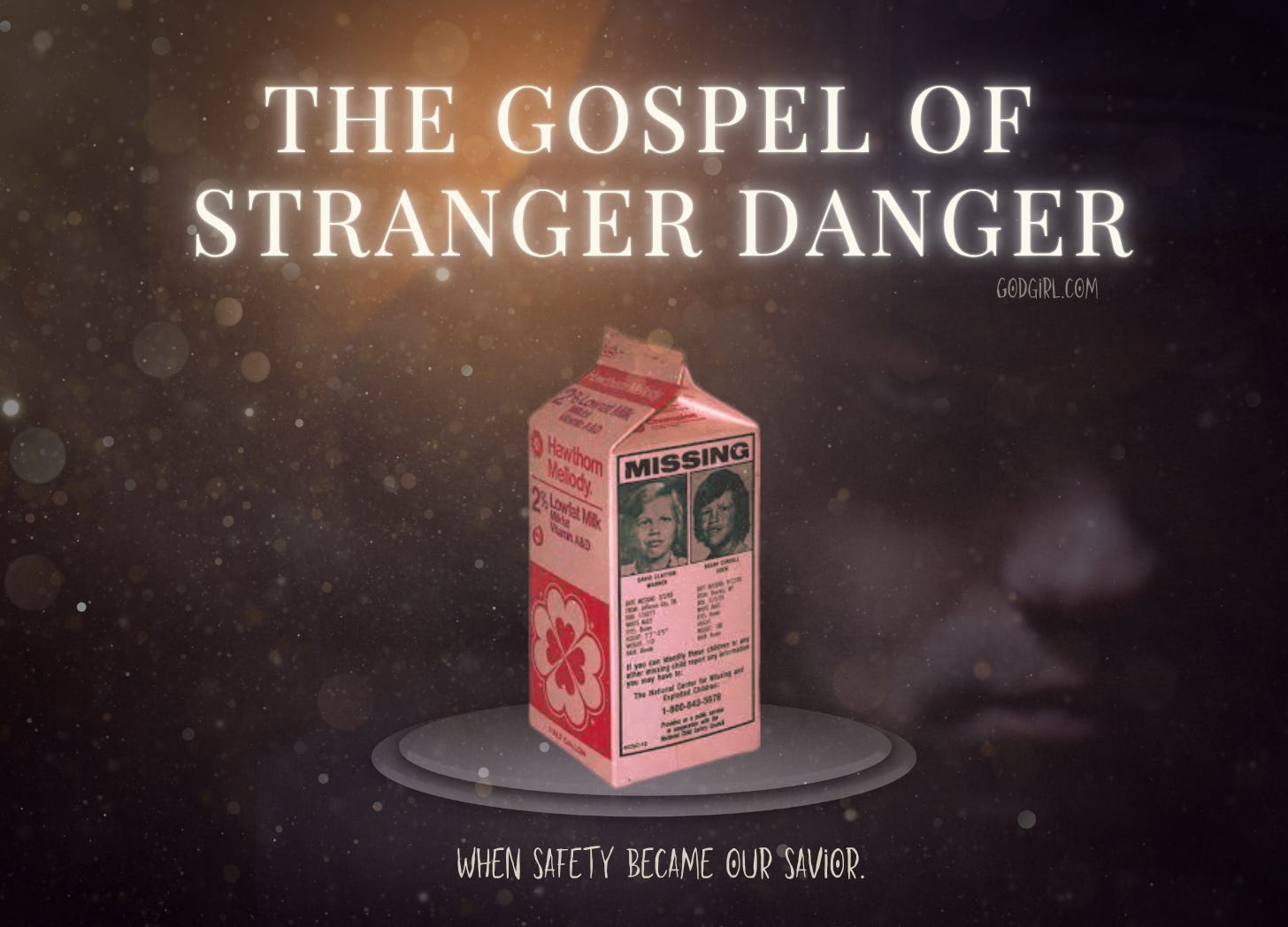

During the late 1970s and early 1980s, America was gripped by moral panic, when media, politicians, and parents became convinced that child abductions by strangers were skyrocketing, even though data showed most child abductions were by family members. Still, faces of missing children on milk cartons, the nightly news, and public-service campaigns burned a single message into our collective imagination:

Don’t trust anyone you don’t know.

We learned it: Don’t trust anyone you don’t know. Turns out, we should’ve been more worried about the people we did know. But the phrase ‘stranger danger’ still became the anthem of a generation. Meant to protect us, it actually formed us into its isolating likeness: fearful, suspicious, and distrusting. We learned the only way to stay off the milk carton was to avoid eye contact, small talk, and white vans.

We were applauded by our parents for being careful and afraid, very afraid. We were socially conditioned to see fear as wisdom and anxiety as virtue. In my first year of college, I was so conditioned that I would not leave my apartment after dark because that’s how girls got killed. I was like a reverse vampire, only able to go out in the safety of daylight.

Even after the institutionalized fear finally faded from the headlines, it still lived on in the quiet chambers of our souls. Teaching us something decidedly different from the true Gospel.

The architecture of avoidance

As believers, we internalized it, baptized it in Christian ‘caution,’ and carried it into adulthood as a kind of anxiety compass—one that pointed not to true north, but to whatever felt safest.

Now, decades later, its residue still holds onto us like cling wrap charged by the static of fear—thin and suffocating. It seals us in while convincing us we’re being protected. We’ve mistaken the airlessness for safety. And somewhere along the way, we learned to equate goodness with guardedness, wisdom with withdrawal, safety with suspicion.

Today, we move through the world as if we are braced for an attack any minute. We avert the eyes of strangers. We imagine them as NPCs, incapable of thought, or love, or being loved by God. We sit beside them on airplanes, in pews, in checkout lines, and simply ignore the imago dei.

Ok, maybe we smile but without seeing. We might converse, when necessary, but without connecting. Our faces are polite masks of self-protection.

It’s not like we’ve stopped believing in the Great Commission; we’ve just stopped believing we’re safe enough to practice it.

We mistakenly, or subconsciously, believe that we are tasked with avoiding strangers, and in the process, we unwittingly have avoided the risk of loving them. We see others as interruptions, threats, or, at best, a type of computer-generated extra who is just moving through our personal storyline to give it an air of reality. In the name of prudence, we have built an entire Christian subculture on the architecture of avoidance.

Unholy Isolation

The tragedy is that our isolation feels holy. We call it discernment. We call it protecting our children. But in reality, it was spawned from the subterranean fear planted in our childhood; a fear that the world beyond our walls is dangerous and that vulnerability, anywhere, is naïve.

It’s the disconnect between our mental reality and our soul’s design. The triune God made us in His image—relational, generous, open-handed, fearless. When we cut ourselves off from seeing His image in others, something in us starts to die because the human heart was not built to thrive in a colony of unbelonging.

The gospel offers no version of salvation that avoids humanity and deems them unsafe, dangerous, or inconvenient.

Jesus did not practice social distancing from strangers; He drew near. He saw their faces. He touched the leper, ate with tax collectors, and wept in public places. The Incarnation itself is the death of “stranger danger.” God stepping into the unsafe world to prove that love is stronger than fear. How does that exist in a world that tells you strangers are dangers?

The tragedy is that we have traded that incarnational posture for a self-protective one: taking no notice of strangers, categorizing people as “crazy” or “problematic,” or non-existent, calling it ‘boundaries’ when it’s really avoidance. We’ve forgotten that every face is a chance to bear witness to the God who has not turned away.

Healing Our Anxiety

If we want to heal our subterranean anxiety, we have to repent not just of indifference but of hesitation. We have to rehumanize the world, one soul, one moment of eye contact, one word of kindness, one small risk of love at a time. Because only when we love the stranger do we remember the One who first loved us.

And when we dump the stranger danger mantra in favor of the Gospel of Jesus Christ, something amazing happens. The tension we’ve carried for years—the worry about what to say, how we look, whether we fit in—starts to fade. The fear that once kept you guarded gives way to something freer, lighter. When you start to see others as image-bearers of God, you finally stop seeing yourself as auditioning for acceptance. The anxious self-consciousness that once kept your joy and love locked inside you moves out and makes room for the Spirit to bloom. You no longer feel out of place anywhere! I mean, anywhere! You are in your place wherever you are, sharing the love of God, and fearlessly.

Field Testing Enemy-Love

The Stranger Danger Illusion (a short Bible study on the topic)

Matthew 5 : 43–48

“You have heard that it was said, ‘Love your neighbor and hate your enemy.’ But I tell you, love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you, that you may be children of your Father in heaven. He causes his sun to rise on the evil and the good, and sends rain on the righteous and the unrighteous. If you love those who love you, what reward will you get? Are not even the tax collectors doing that? And if you greet only your own people, what are you doing more than others? Do not even pagans do that? Be perfect, therefore, as your heavenly Father is perfect.”

Why we’re testing this passage:

The “stranger danger” reflex is older than news cycles. It’s the ancient habit of dividing humanity into safe and unsafe, ours and theirs. But Jesus dismantles that boundary by tying love not to familiarity but to likeness with the Father.

1. Start with the contrast

“You have heard… but I say.”

“Hate your enemies” was a common rabbinic and cultural teaching of the time, shaped by nationalism and the belief that loving one’s own implied rejecting outsiders (especially Gentiles and oppressors like Rome).

How does Jesus contrast that teaching?

How does His command expose the lie at the heart of the “stranger danger” reflex—that safety is found in separation rather than resemblance to God?

What is the inner motive behind loving only those who love us?

2. Examine His logic of likeness

“…that you may be children of your Father in heaven.”

What makes us children of God here?

How does the Father’s impartial generosity (sun and rain) become the model for ours?

Why might Jesus use the weather, something constant and impartial, to dismantle the idea that danger lies in difference?

In what way does divine likeness replace the illusion that holiness requires distance from the “stranger”?

3. Define the verbs

“Love… pray… greet.”

Agapaō here means deliberate, active goodwill—not affection or approval, but the choice to seek another’s good. Prayer extends that goodwill into the unseen, and greeting brings it into embodied presence. These verbs are less about feeling and more about participation in divine action.

Why might Jesus choose verbs that involve action rather than emotion?

How do these verbs retrain the reflex to avoid or ignore strangers?

What happens to the “stranger danger” instinct when love becomes a practiced motion instead of a managed feeling?

4. Test the perfection clause

“Be perfect, therefore, as your heavenly Father is perfect.”

The Greek teleios means whole, mature, complete. Enemy-love doesn’t just raise moral standards; it restores wholeness—God’s image made visible in us.

How does this call to completeness expose how partial the “stranger danger” mindset really is?

In this context, what’s the difference between human perfectionism (controlled purity) and divine wholeness (inclusive love)?

How does this verse redefine spiritual maturity—not as purity from others, but as resemblance to the God who includes them?

Field Note

The test isn’t whether you feel affection for your enemy, but whether your actions resemble your Father’s weather—steady, impartial, and life-giving even to those who still look like strangers.