Doorbell Theology

the panic we don’t talk about

The doorbell rang this morning at 5 am. It was dark. I was fast asleep. And it pierced my peace like a steak knife through Saran Wrap, slicing and pulling me into its jagged maw.

My first thought was that it was a murderer there to murder me. Of course, murderers always ring the doorbell.

I sat up with a start, looking for the nearest heavy item I could use as a weapon.

My husband, of course, slept through the whole attempted assassination, as if it never happened (which it didn’t), at least not the murder part, but the doorbell did indeed ring on its own. There wasn’t even a person there. Electronic doorbells: the physical trainer of the heart.

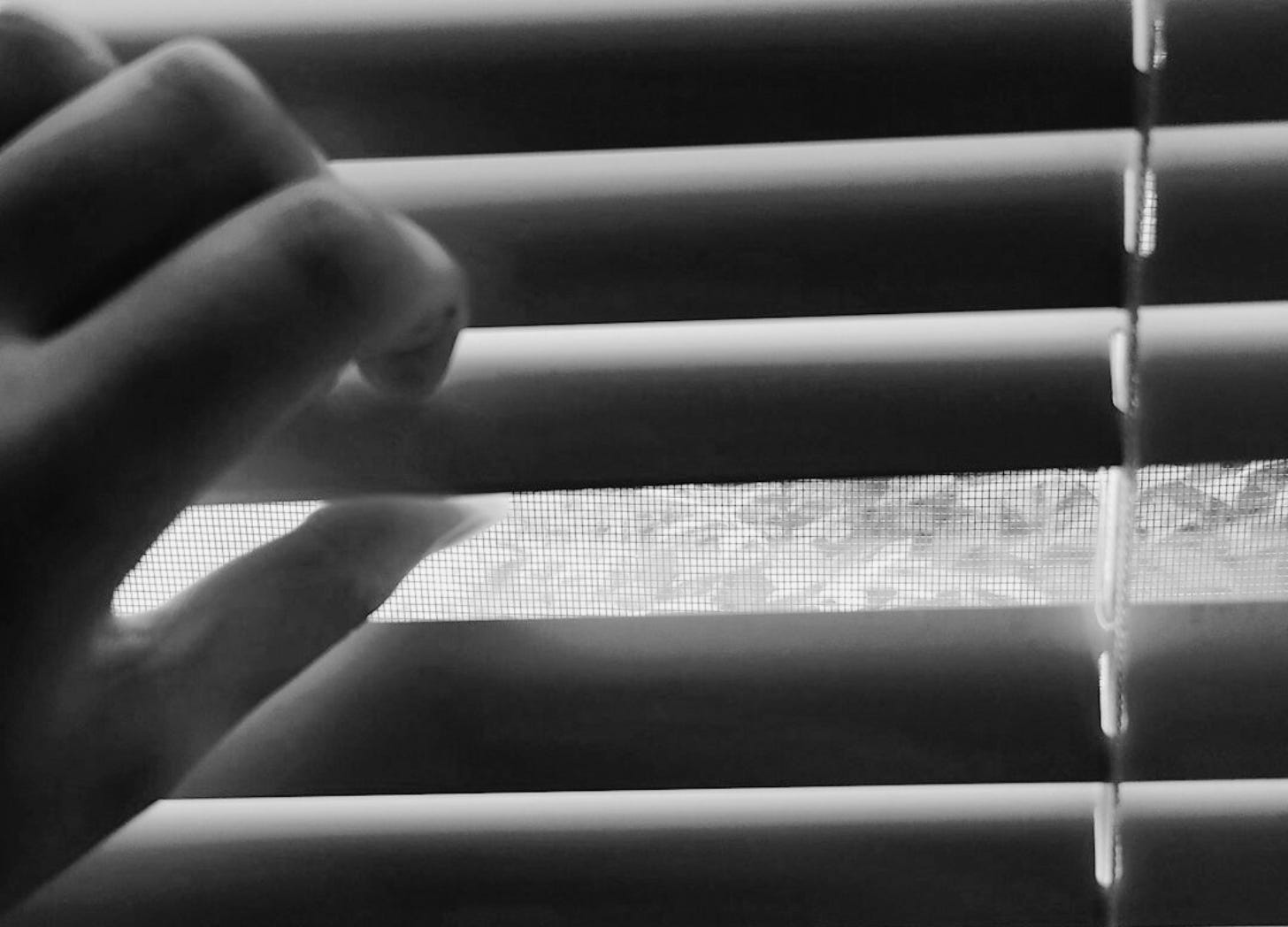

If you are a woman, then you can probably relate. No good news comes to your door at 5 am, wanting to be let in. Only criminals and crises make a sound at 5 am. So why then do I feel the same sense of panic at noon, 2 pm, or 3:30? Why do I immediately fear the worst and go into hiding in the middle of the day? Literally, ducking behind the couch so they can’t see my shadow. Turning down the music so they don’t know I’m here. It’s a thing, right? I’m not alone. Say I’m not alone!

I believe women all over the country fear the unexpected knock at the door. Why is that? My conclusion: formed by a constant feed of worst-case scenarios, the modern woman has been discipled more by threat-awareness than by trust.

True crime podcasts, local neighborhood crime apps, the 24-hour news cycle that profits from fear, social media stories that major in danger because bravery doesn’t go viral, but terror sure does. Sociologists say we’ve created a collective fear culture. Meaning we’ve quietly developed the recipe for a shared expectation of harm.

And in a world like that, the unexpected knock is made from:

one part uninvited = unsafe

one part surprise = suspicious

another part “the unknown” = enemy

We don’t fear the doorbell because we’ve been burned by it so many times. I mean, how many bad guys have knocked at my door to date? Zero, that’s how many. Of course, I judge that based on the fact that after ringing, they didn’t then try to break in, as I imagined they would. So experience should make me feel safe, but something more powerful disagrees and drives me to doorbell anxiety.

For centuries, women have carried messages, delivering them to our children and friends, saying:

Don’t walk alone.

Don’t open the door.

Don’t trust strangers.

Don’t get caught off guard.

It’s our inherited wisdom from years of darkness and danger. But when we internalize without thinking, it becomes insidious, a kind of inherited hypervigilance that keeps us in a constant state of surveillance and anxiety.

The result is that our nervous systems coded potential “unexpected man at the door” as “probable harm.”

And because I can’t leave anything alone until I’ve traced it down to its spiritual root system, I’ll tell you where I think the problem finds its origin: anxiety is our functional theology, just not a biblical one.

The female fear of the doorbell is not about crime; it’s about living as if we have to be omniscient to be safe. That’s our acted-upon theology. It’s not really the danger we fear; most of us have had little to no experience with real danger at the door. But it’s the fear of not knowing that drives us into hiding, fed by our discomfort with not being omniscient.

See, anxiety is always practicing its own theology, even when we don’t realize it. And the theology of fear says: You have to know everything to be safe. You have to anticipate the threat. You have to be omniscient for your world to be okay. Not because we think we’re God, but because the body acts like we have to fill in for Him in times of threat. It believes the knock means, “You’re on. You need to evaluate, interpret, predict, and protect. Get it right or get dead.”

But, dear reader, God has not made you responsible for foreknowledge. He has never asked a single human being to anticipate every threat or avoid every surprise.

But as a theology of self-protection, anxieties counter arguement to this truth is, “If I can just predict the danger, then I can prevent it from endangering.”

The gospel, however, tells a different story: “You are not the Watcher of the World. You are watched over.” The Lord neither slumbers nor sleeps, so you can. Even at 5 a.m., when the bell rings. Even when the unknown pushes its way into your sleep. Even when you didn’t know they were coming, and they’re at your door now.

The answer to the unexpected knock is not to just calm down and get over it. And it’s not a heroic decision to answer the door. The answer is a theological handoff in which you give God back the job your fear tried to take from Him.

Sure, you can and should retrain your nervous system, but that’s secondary. Helpful, but not foundational. Your freedom comes from reassigning the task of omniscience by naming the unsaid belief, and saying something like, “Not my job. I’m not gonna act like if I don’t know who’s there, then it’s not safe.” In other words, I am no longer going to believe that if I’m not omniscient, then I’m not safe.

Your nervous system calms the fastest when it isn’t carrying this stolen responsibility. When you take a deep breath and let your brain know there is no imminent threat, and then let your spirit remember who actually guards the threshold, you create a kind of holy co-regulation.

See, I’ve figured it out: the door isn’t actually the problem. The takeover is. And the moment you give the job back, that particular fear loses its authority in your life. And maybe that’s why the bell rings so loud. Not because danger is actually there, but because we’ve been living as though we’re the ones responsible for knowing what’s coming next.

A lot of what I’m writing about lately lives in this tension between vigilance and trust, between taking over and handing back.

Fruitful is where I’ve been exploring that tension more fully: what grows in us when God is allowed to do His work, and we’re finally free to do ours?

“You are not the Watcher of the World. You are watched over.” Way good Hayley!